Yoga is not only about the poses we do – so called asanas. In order to fully understand the entirety of the yoga philosophy, let‘s have a look at The Eight Limbs of Yoga mentioned by Patanjali, the father of modern yoga. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras present the basic principles of yoga in 196 short aphorisms, called sutras (formulas). The Yoga Sutras delineate the vision, practices, techniques and experiences that arise on the path of yoga. The Eight Limbs of yoga are often regarded as the heart of the Yoga Sutras.

But: What Yoga actually is?

Yoga, as described by Patanjali, sets us a spiritual goal and shows us the means to achieve it. In yoga we are concerned with the transformation (parinama) of body and mind. It helps us to systematically transform the various layers of our being. To begin with: Yoga talks about creating the best possible relationship with the external world – with objects and beings.

Patanjali’s Yoga is one of the most systematic approaches to understanding the mind, which provides us with the tools to control the mind (citta), transform it and finally transcend the mind.

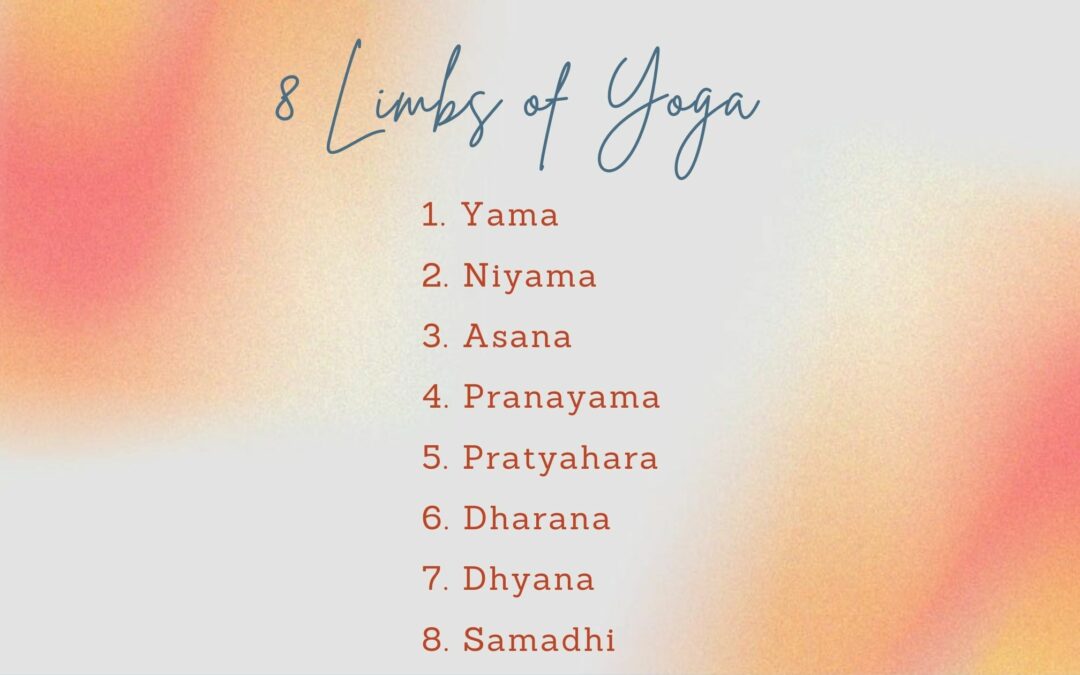

What are the 8 Limbs of Yoga?

The 8 limbs in yoga are: 1. Yama · 2. Niyama · 3. Asana · 4. Pranayama · 5. Pratyahara · 6. Dharana · 7. Dhyana · 8. Samadhi. Let’s explore them:

1. YAMA – Restraints, moral disciplines or moral vows

As the first limb, Patanjali mentions Yama – practices of social discipline which regulate the functioning of the mind in our relationships with others.

Patanjali lists the following 5 yamas:

- Ahimsa (non-violence),

- Satya (truthfulness),

- Asteya (non-stealing),

- Brahmacharya (right use of energy) and

- Aparigraha (non-greed or non-hoarding).

Yamas are not principles but practices. Firstly, yoga is not meant to impose anything on us, including rules of conduct. Secondly, the yamas are meant to be a measurable action, not rules that one adheres to in the privacy of one’s home. Thirdly, these practices are done for specific purposes, which Patanjali clearly states in the individual sutras. The context of these indications is psychological (obtaining a certain state of mind), not ethical. Fourthly, like any practice in yoga, yamas are initiatory in nature, meaning that by initiating one’s yama, one is making a decision to carry out certain tasks and thereafter every decision we make, every action we take, should be preceded by the question: “Does this serve the task I have set myself or not?”

The procedure for the practice is very simple: you observe various aspects of your life in the context of a particular yama. Once you have diagnosed the difficult areas you decide on a specific change in that area and then enforce your decision.

2. NIYAMA – Positive duties or observances

After the practices of social discipline, Patanjali describes the practices of individual discipline – the niyamas. While yamas regulate our functioning in relationships with others, niyamas concern our relationship with ourselves and, as a kind of purification practice, are a direct preparation for further practice (asanas, pranayama, pratyahara and concentration-meditation practices).

Patanjali describes the following 5 niyamas:

- saucha (cleanliness),

- santosha (contentment),

- tapas (discipline),

- svadhyaya (self-study or self-reflection, and study of spiritual texts) and

- isvara pranidhana (surrender to a higher power).

3. ASANA – Posture

The issues related to asanas in the Yoga Sutras are perhaps the most difficult to discuss for one simple reason: for some, asanas are physical exercises, while for Patanjali they are meditative positions. According to his teaching, asana should be stable and comfortable.

Asanas influence the practitioner on three levels:

- the physical level,

- the mental/spiritual/psychic level,

- the energetic level.

The quality of relaxation, of comfort – sukham – is crucial in the practice, because it is freedom from tension that is freedom from our conditioning.

According to Patanjali the yoga postures must comply with the following criteria: stability, freedom from tension, freedom from unnecessary effort, and concentration on prolonged and free breathing.

4. PRANAYAMA – Breathing Techniques

The foundation of our practice is the breath. The more aware someone is of the breath, the stronger their inner life. It is necessary to accompany one’s breath with awareness during inhalation and exhalation, as well as ultimately also during pauses after inhalation and exhalation (internal and external retention).

Stopping the uncontrolled movement of the mind during inhalation and exhalation while abiding in a perfect (stable and comfortable) position is pranayama. The term ‘pranayama’ has two parts: prana and yama. Yama means control, prana means vital force or lifeforce energy. Pranayama is therefore the practice of controlling the flow of prana (vital force). A second translation of the term breaks down the term ‘pranayama’ into prana and ayama – expansion, spreading. We can then translate the yoga technique as the practice of spreading prana.

5. PRATYAHARA – Sense withdrawal

The practices of sense withdrawal (pratyahara) are a less frequently considered part of yoga, but provide us with an interesting tool for working with emerging impressions. Patanjali defines pratyahara as follows: The withdrawal of the senses occurs when we separate the senses from potential objects. The author of the Yoga Sutras assumes that the natural state of mind is “sattva”, and therefore means lightness, peace, harmony. This state, however, can be disturbed when the mind becomes distracted. One of the most common causes of distraction are the senses, which direct our attention to external objects.

Practising Pratyahara we do not analyse impressions, we do not try to control them, we unconditionally accept even those impressions that we do not like. We do not judge whether these impressions are positive or negative, nor do we name them. In this way, we enter a fresh state of mind in which it is fully relaxed yet attentive. On the other hand, we learn to react in a neutral way even to unpleasant impressions, which is later applied to the way we react in everyday life. When we learn to work in this way, lying down or sitting in relaxation, we can apply it to any situation in which we find it difficult to distance ourselves from the onslaught of impressions.

6. DHARANA – Focused Concentration

Dharana means ‘focused concentration’. Dha means ‘holding or maintaining’, and Ana means ‘other’ or ‘something else’.

Each limb of the Eight Limbs of Yoga prepares us for the next. Whereas Pratyahara teaches us to withdraw our focus from the external to the internal, the practice of Dharana teaches us to ‘zoom in’ so we’re able to focus on one thing alone.

7. DHYANA – Meditative Absorption

The seventh limb is ‘meditative absorption’ – when we become completely absorbed in the focus of our meditation, and this is when we’re really meditating. All the things we may learn in class are merely techniques in order to help us settle, focus and concentrate. An example of how the 8 limbs build on each other: Asana practice makes our body strong, healthy and pain-free so that we can sit cross-legged in meditation without discomfort.

8. SAMADHI – Bliss or Enlightenment

Samadhi is the final step of the journey of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras.

Breaking the word in half, we see that this final stage is made up of two words; ‘sama’ meaning ‘same’ or ‘equal’, and ‘dhi’ meaning ‘to see’. There’s a reason it’s called realisation. It’s because reaching Samadhi is not about escapism, floating away or being abundantly joyful; it’s about realising the very life that lies in front of us. The ability to ‘see equally’ and without disturbance from the mind, without our experience being conditioned by likes, dislikes or habits, without a need to judge or become attached to any particular aspect; that is bliss.

So is Yoga just about taking poses?

Many people only know the asana practice, but yoga is so much more. The 8 limbs show that yoga doesn’t just take place on the mat, but is a philosophy of life. It is the path of practice, of constant practice to unfold its holistic qualities.

How can you apply the limbs in a spiritual practice?

Ideally, what we are looking for in a spiritual practice is transformation, not rigidity. We can treat the Eight Limbs of Yoga in relation to the conscious choice we make to engage with our growth, honesty, discipline, and transformation. When looked at through this lens, the Eight Limbs become a way for us to check in with all of our levels of engagement, from the level of the world and the people around us to the way we relate to our inner being. After all, experiencing the world is one of the primary ways that we know we are alive; we live in a world that is interconnected, interdependent, and vibrantly diverse. If we live only in our own thoughts, we become cut off from experience, where we actually live.

Inspired by the book “One Simple Thing” by Eddie Stern, we can interpret the Eight Limbs in the context of the following behaviours:

- Yama: I consciously choose to make my interpersonal interactions thoughtful, loving, and respectful.

- Niyama: I consciously choose to dedicate myself to my spiritual practices and disciplines.

- Asana: I consciously choose to take care of my body and mind through practising postures.

- Pranayama: I consciously choose to regulate and balance my breath and nervous system through breathing practices.

- Pratyahara: I consciously choose to pay attention to the awareness that lies below and is the power behind my sense organs.

- Dharana: I consciously choose to direct my focus and attention, and to refocus myself when necessary.

- Dyana: I consciously choose to move my mind toward absorption in my objects of focus and attention.

- Samadhi: I consciously choose to shift my perception toward an experience of unity consciousness.

The Eight Limbs as a whole are defined as practices that remove the impurities that cloud our field of consciousness, the spiritual liberation from the shackles of our conditioned mind. The goal of yoga is for our being to rest in its own self and not be lost through identification with the changing nature of the world. This is what is called freedom in the yogic tradition.

And it all starts with the path of practice. 😊

Sources:

Eddie Stern – “One Simple Thing: A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How It Can Transform Your Life”

Maciej Wielobób – “Psychologia jogi”